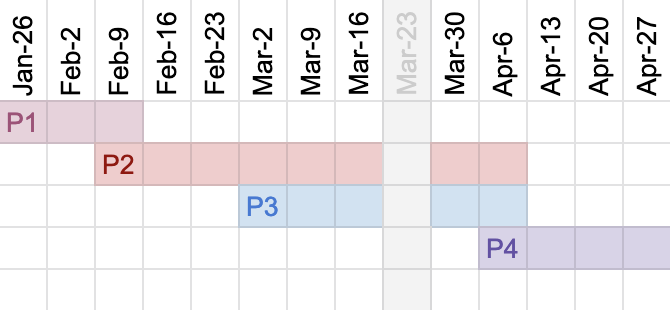

1:30–1:40 — Fill out this brief survey and join this Slack group

1:40–1:55 — Introductions: How does your practice incorporate gathering?

1:55–2:10 — Group Agreement

2:10–2:35 — Review Syllabus

2:35–3:35 — Read: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction

3:35–3:50 — break

3:50–4:25 — Intro: Collection, Website, Website Hard Copy, Performance Lecture, Kiosk

4:25–4:30 — Sign up for Kiosks

4:30–5:00 — P1 begins →

5:00–5:30 — writing exercise

For next week...

- create 3–5 ideas

- for each idea, include at least 10 entry examples

- link your questionnaire in our shared spreadsheet

- Read: “UNLICENSED: Shanzhai Lyric” (we will not discuss this reading; it provides background on our guest speakers next week)

1:30–3:00 — Guest: Shanzhai Lyric & Canal Street Research (Ming Lin & Alex Tatarsky)

3:20–4:00 — Demo: Create a microsite with custom domain on Github Pages

4:00–5:30 — Reviews: small group

For next week...

- Refine 1 idea and import at least 25 entries into a spreadsheet. If you’re crowdsourcing this, please prepare to present your method of dissemination.

- purchase a domain name

- prep Community Memory Kiosk

- Try to attend Saturday’s “How can we gather now?” event, hosted by Prem Krishnamurthy. RSVP here.

1:30–2:00 — Presentation: Community Memory Kiosk

2:00–2:05 — rearrange Kiosk groups

2:05–2:15 — P2 begins →

2:15–4:15 — Demo: (Alvin) Google Sheets as CMS

4:15–5:30 — Reviews: small group

For next week...

- Next week’s class will be pushed by 1.5 hours, 3:00–7:00pm.

- Can 1–2 volunteers switch to the last Kiosk group on April 20th?

- Read: Shaina Anand, “10 Thesis on the Archive” (begins on PDF p.41)

- Begin to code your website. Your spreadsheet should be populating your website.

- Prepare to show a website in progress. Include digital sketches to supplement your in-progress work.

3:00–3:45 — Discuss: Shaina Anand, “10 Thesis on the Archive”

3:45–7:00 — Reviews: small group

For next week...

- prep Community Memory Kiosk

- Read: “Cultivating Care” and “Sculpting Soil” (we will not discuss this reading; it provides background on our guest speaker next week)

- continue working on your website

- add a link to your website in our shared spreadsheet

2:00–3:30 — Guest: Asad Raza

3:30–5:30 — Reviews: small group

For next week...

- Next week’s class will be pushed by 1.5 hours, 3:00–7:00pm.

- continue working on your website; it should live online with a domain name

- next week’s class will be all-class, mid-project presentations

3:00–6:30 — Reviews: P2 mid-project presentations (all class)

6:30–7:00 — P3 begins →

For next week...

- your website should be online with a domain name

- your website sketches should be live in code, rather than in a prototyping tool

- create sketches for your website hard copy

- Note: I’ve removed our reading discussion next week so we have time to talk about project updates

- Read: (optional) Kritika Agarwal, “Doing Right Online: Archivists Shape an Ethics for the Digital Age”

- Read: (optional) Lara Putnam, “Transnational and Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows they Cast”

1:30–3:00 — Demo: Print CSS

3:00–5:30 — Reviews: small group

For next week...

- next week’s class will be remote!

- continue refining your website

- create 2 versions of your website hard copy

1:30–3:00 — Demo: (Alvin) Google Sheets and InDesign Scripting

For next week...

- continue coding your website

- continue working on your website hard copy

- prep Community Memory Kiosk

There are optional office hours this week on Monday, March 21st and Wednesday, March 23rd. Sign-up in our shared spreadsheet.

https://rutgers.zoom.us/my/ms3014 with code 727318

For next week...

- note that next week’s class has been moved up 2 hours and will begin at 11:30am

- finalize your website and website hard copy

- Read: “Kameelah Janan Rasheed on Learning and Unlearning” (we will not discuss this reading; it provides background on our guest speaker next week) finalize your website and website hard copy

11:30–3:00 — Guest: Kameelah Janan Rasheed

11:30–3:00 — Reviews: P2 and P3 final presentations

3:00–3:30 — P4 begins →

For next week...

- please add your website link to our shared spreadsheet

- prepare your Kiosk

- Watch: Morehshin Allayhari’s “Physical Tactics for Digital Colonialism” and Ruben Pater’s “Untold Stories”

- create a thorough outline and/or storyboard for your performance lecture

2:00–2:45 — Discuss: Morehshin Allayhari’s “Physical Tactics for Digital Colonialism” and Ruben Pater’s “Untold Stories”

2:45–5:30 — Reviews: small group

5:30–6:00 — performance lecture by M.C. and Cat

For next week...

- prep Community Memory Kiosk

- be ready to present a draft run-through of your performance lecture

- prepare any audio, visual, or example slides

2:00–5:30 — Reviews: small group

For next week...

- Watch: “On Closed Boxes”, and Read: “Artforum 500 Words” and “Why I Don't Talk About ‘The Body’” (we will not discuss these; it provides background on our guest speaker next week)

- prepare your final performance lecture

3:00–6:00 — Guest: Gordon Hall

3:00–4:00 — four performances

4:00–4:15 — intermission

4:15–5:15 — four performances

5:15–6:00 — discussion with Gordon Hall

6:00–7:00 — drinks!

For first- or second-year graphic design students. On Gathering is part studio, part seminar about gathering in its material and social forms, a collection of disparate objects and the communion of people, respectively. Through hands-on design projects, readings, and discussions, students will develop works around four project prompts about a (1) collection, (2) website, (3) website hardcopy, and (4) performance lecture. In reference to Ursula K. Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, we will position the first tool as the basket, a tool for communion, rather than the spear, a tool for domination. In doing so, we will question the curatorial and political role of the collector in this digital age of excess, as well as the form of the container of these collections, and how they might be shared with specific communities. Technical exercises include an introduction to Github, Google Sheets as CMS, InDesign scripting, and Print CSS. This class is intended for those with a working knowledge of HTML and CSS. JavaScript would be helpful but not required. Completed projects are expected to be technological in nature.

This course itself will be a gathering. Multidisciplinary practitioners will visit and lead discussions with students. This semester we welcome Ming Lin and Alexandra Tatarsky (Canal Street Research and Shanzhai Lyric), Kameelah Janan Rasheed, Asad Raza, and Gordon Hall (Center for Experimental Lectures).

With each prompt, aim to transform your project, altering its meaning and/or its function through choices concerning content, material, visual form, language and sequence. Your decisions are not neutral. Be prepared to articulate why you have compiled this particular collection and its relationship to a larger social context.

See full syllabus ⤻

Land Acknowledgement Statement

The Yale School of Art and Yale University acknowledge that indigenous peoples and nations, including Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic, and the Quinnipiac and other Algonquian speaking peoples, have stewarded through generations the lands and waterways of what is now the state of Connecticut. We honor and respect the enduring relationship that exists between the peoples and nations and this land. (sourced from https://www.art.yale.edu/about/land-acknowledgement)

Even for our video calls, Zoom relies on servers at Equinix data centers in Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Melbourne, New York, Tokyo, Toronto, Silicon Valley & Sydney, according to Rory Solomon, Assistant Professor at the New School. Let’s discuss: Why do we recognize the land? “To recognize the land is an expression of gratitude and appreciation to those whose territory you reside on, and a way of honoring the indigenous people who have been living and working on the land from time immemorial. It is important to understand the long-standing history that has brought you to reside on the land, and to seek to understand your place within that history. Land acknowledgements do not exist in a past tense, or historical context: colonialism is a current ongoing process, and we need to build our mindfulness of our present participation. It is also worth noting that acknowledging the land is indigenous protocol.” (sourced from www.lspirg.org/knowtheland) More information can be found here: native-land.ca

Land acknowledgement statements are meant to be crafted in conversation with representatives of the respective nations. Some organizations believe that this should be paired with fiscally contingent plans as the start of reparations. To my knowledge, it is not clear if Yale SoA has reached out to members of the Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic, and the Quinnipiac. I still choose to add this land acknowledgement to our syllabus in order to begin this conversation with you, our students, as a small attempt towards this goal.

→ P1: Collection

Gather at least 50 entries for your collection. This is an important phase, since you will be working with this body of content for the duration of the semester. For the next several weeks, you will add this to a spreadsheet that will populate your website and publication. Your spreadsheet should include the appropriate taxonomy and metadata for each entry (title, author, date, description, caption, source, etc.)

- Why does this collection need to exist?

- What is the purpose of your collection?

- What is the critical edge?

- What void does this fill?

- What entries are you gathering?

- Is it media-specific? (e.g. quotes, images, PDFs, etc)

- Is there a time period?

- What metadata do you need for each entry?

- How will you gather it?

- Is it crowdsourced?

- If so, how is it disseminated?

- newsletter?

- social media post?

- airdrop?

- voicemail?

- billboard?

- pigeons?

- Where will you ask it? (note the difference between SoA vs. Reddit)

- How will you cite contributors?

- Or is it individually sourced?

- Will you map your learning trail?

- For whom are you gathering?

- Is it for an organization?

- Is this a community you’re a part of?

- References

- Saidiya Hartman’s notion of “critical fabulation”

- Radical Google Docs

- Info Activism using Google Drive

- Spreadsheet Directories

→ P2: Website

Create a website with your collection. You are encouraged to use the Google Sheet as a Content Management System (CMS) for your microsite, but you may also choose to manually input entries into the text editor of your choice.

Whether crowd-sourced or independently collected, entries in a cloud-based spreadsheet allow for accessibility, dispersibility, and the immediacy of real-time updates. When digital spreadsheets were first released in 1985, they were considered a liberatory technology—“functional programming for the masses.” However, as noted by the father of hypertext Ted Nelson, “conventional data structures—especially tables and arrays—are confined structures created from a rigid top-down specification that enforces regularity and rectangularity.” A bespoke microsite is not restricted by the affordances of a spreadsheet, and so, when flowing in the entries from your tables and rows, consider how this new container will support, and frame, its gathered goods.

- How does the design of your website differ from that of your spreadsheet?

- Is it more clear or convoluted?

- Are specific entries highlighted?

- Is it dynamic or static?

- References

→ P3: Website Hard Copy

Produce a hard copy of your website. You can (1) use Print CSS, (2) blend your spreadsheet with InDesign scripting, (3) manually enter your items into InDesign, or (4) create an alternative publication form. If you speak to a digital archivist, they will state that duplication is key. With a rapidly changing (and degrading) web landscape, to download or export can be an act of preservation and ownership. Changing the form of a collection also allows for different modes of experience and reading. A hard copy is considered to be fixed and static while a soft copy is fluid and mutable. However, both are complementary and are mediated through their respective interfaces.

- How does your website differ from its hard copy?

- Are they clones or complements?

- Are certain elements revealed or hidden?

- How will you change its sequence?

- Will you limit its quantity?

- References:

- Hard Copy

- Library of the Printed Web

- Morehshin Allayari’s Material Speculation: Isis

- David Reinfurt’s Universal Serial Bus

- Werkplaatz calendar

- Rhizome’s The Download

- Sites with Print-on-Demand and PDF Generators

→ P4: Performance Lecture

Create a 10 minute performance lecture of your collection. As an alternative to a slide-based lecture, we will create experimental presentations of the research you’ve collected this semester.

- How might you incorporate the qualities of a performance into a lecture to convey your body of research?

- What is typically understood as a lecture?

- What is typically understood as a performance?

- What type of performances have resonated with you?

- How will your performance lecture be documented and displayed after the event?

- Logistics

- Our final presentation will take place on Saturday, April 23rd.

- Option 1: Use our existing critique format

- Each project has a 30-min slot (10-min presentation, 20-min discussion) with breaks in between.

- Option 2: Create an event

- (5) 10-min presentations

- intermission

- (5) 10-min presentations

- group discussion

- What time of day do you prefer? 3:00–6:00

- Would you like to open this up to the public? Yes

- If so, would someone like to create a flyer, etc. to disseminate info? Paul & M.C.

- References:

→ Community Memory Kiosk

For this one-week group project, please create a community memory kiosk. It should be (1) somewhere in the Atrium (2) with an analog and digital component that (3) allows your peers to contribute content. The Community Memory Project was based in Berkeley, CA in 1976. From their description, they write:

We are placing public computer terminals through which people can freely share information unmediated by censors. Community Memory allows people with no previous computer experience to enter messages, find messages entered by others, and enter responses to what they see. Messages are cross-indexed to related subjects to help people make connections.

The Spring 2021 version of this course was made with support from Laurel Schwulst, Geoff Han, Isaac Nichols, and Rosa McElheny. Thank you to these folx! This course was heavily modified from that version, from learnings from the Spring 2021 students Alvin Ashiatey, Immanuel Yang, Nick Massarelli, Mike Tully, Alex Mingda Zhang, Hannah Tjaden, and Ana Lobo. Extra thanks to Alvin Ashiatey for returning for an additional semester as the T.A.!

Sites by students...

David Jon Walker’s “Course Map Repository”

Junyi Shi’s “Houseplants from the Wild”

Kyle Richardson’s “Grammy’s House”

Lester Rosso’s “Laugh Later”

M.C. Madrigal and Cat Wentworth’s “Endnotes, link tk”

Paul Bille’s “Temporary and Unnamed”

Sam Callahan’s “Mirror as Portal”

Yifan Wang’s “Gathering Robert Adams”

Yuseon Park’s “A Recording Score”

Kyle Richardson, “Grammy’s House” website

Kyle Richardson, “Grammy’s House” performance lecture, photo by Yuseon Park

Junyi Shi, “Houseplants from the Wild” performance lecture, photos by Kyle Richardson

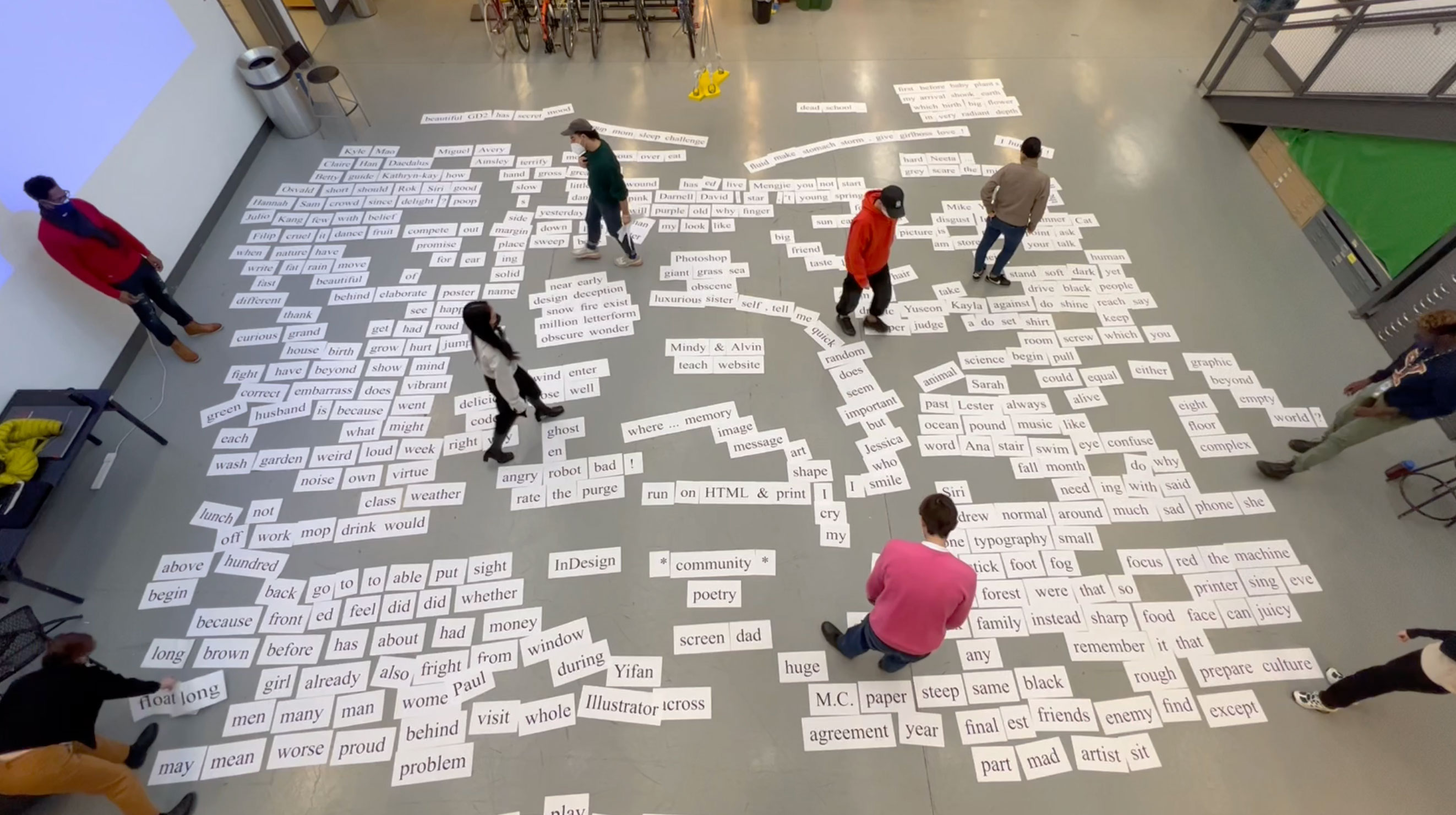

Cat Wentworth, M.C. Madrigal, Yifan Wang, “Community Poetry” installation, screenshot from video by M.C. Madrigal

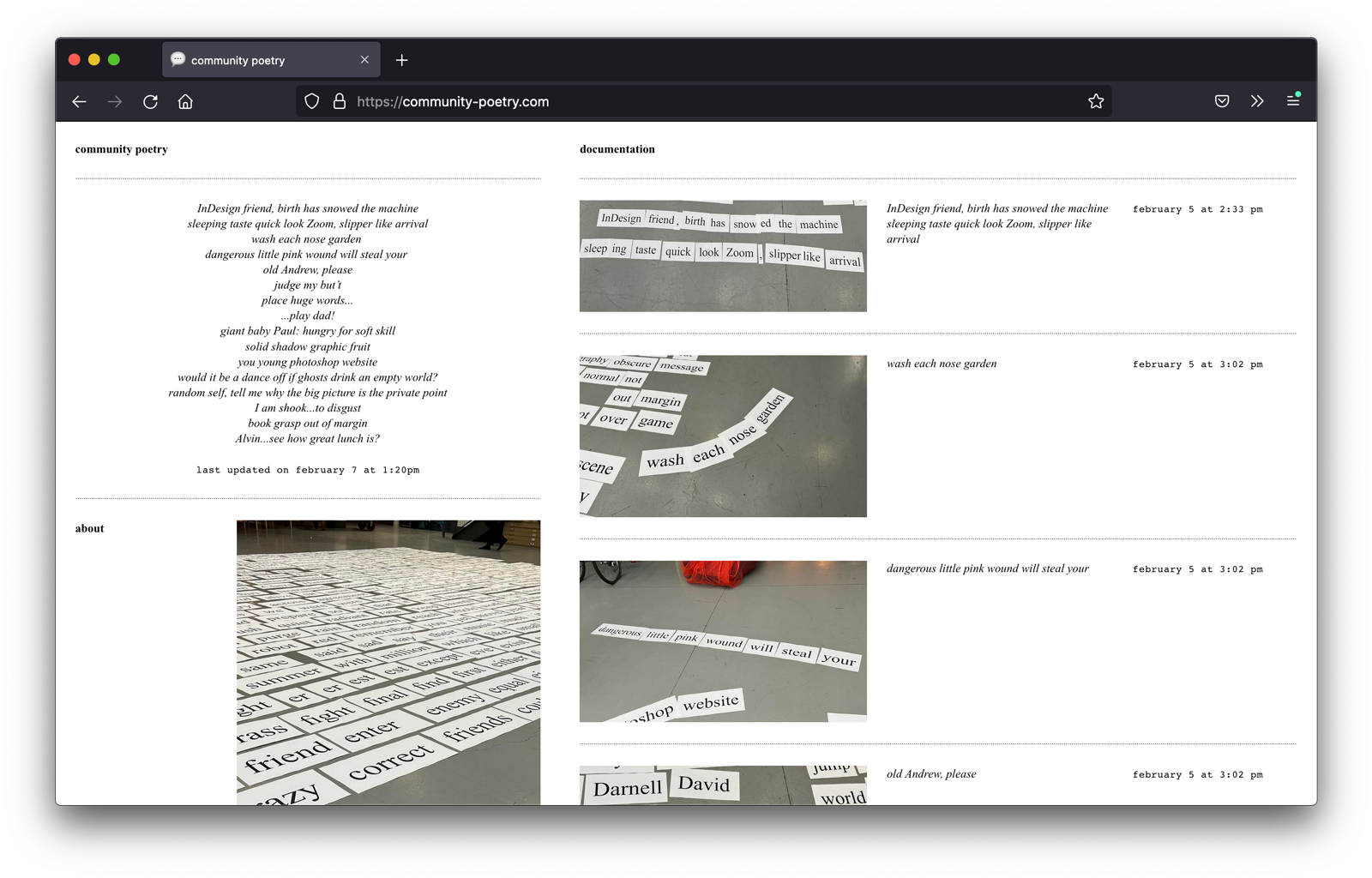

Cat Wentworth, M.C. Madrigal, Yifan Wang, “Community Poetry” website